Questions for Sally McGill

How did you become a scientist/engineer?

As a high school student, when I started thinking about possible careers I realized that I liked being outside and I liked working with maps. My family had done a lot of canoe camping in northern Minnesota, and I had enjoyed being the navigator, matching up the bays and peninsulas on the map with those that I could see in front of me from the vantage point of our canoe. I loved the sense of discovery and exploration of the natural world. These interests led me into geology, where I have continued to explore mountains and deserts, learning how to listen to the stories told by the landscapes and rock formations around me.

What is your job like?

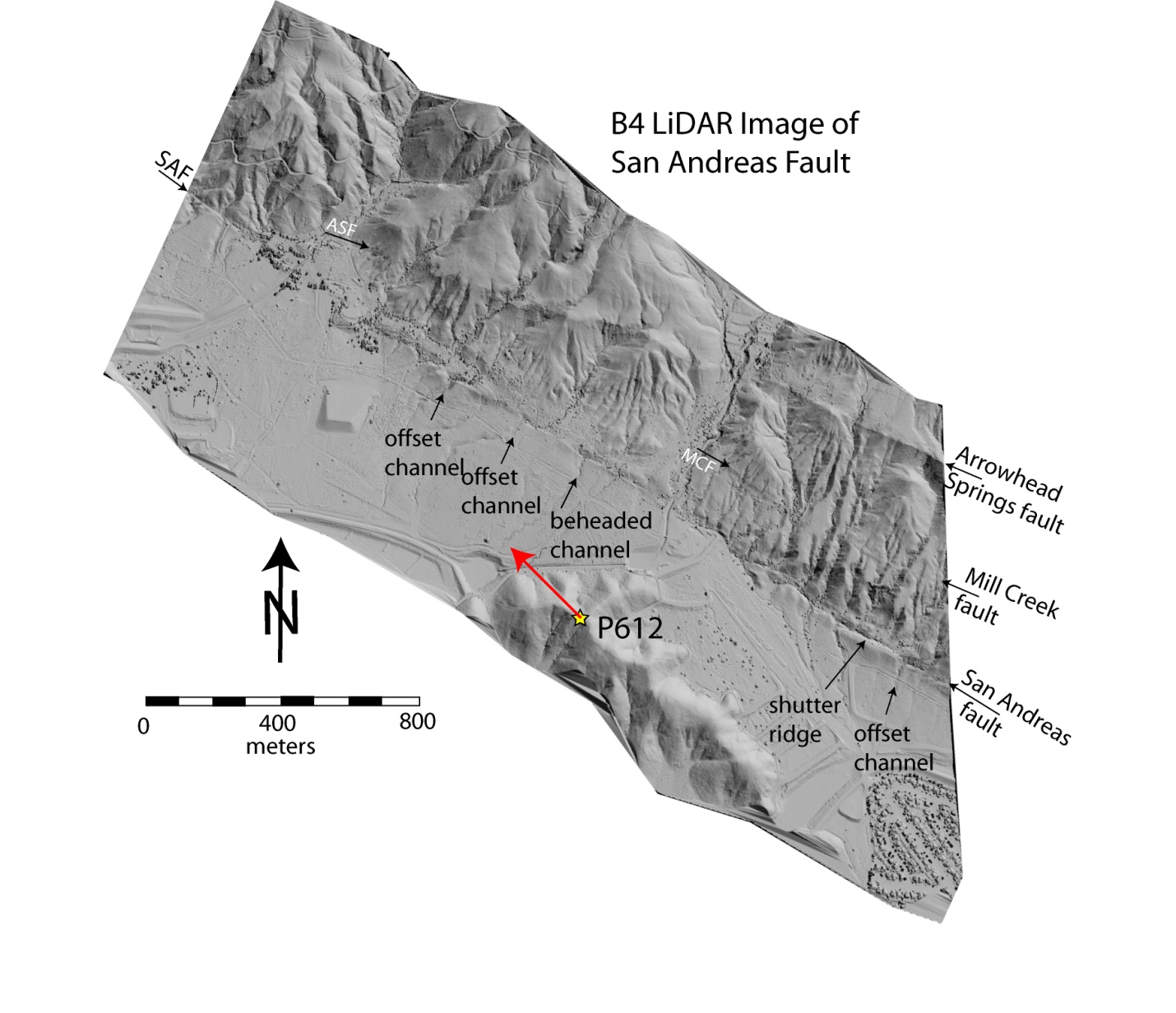

I am a geology professor at California State University, San Bernardino. When I was in college I had told myself that I didn't want to have the same career my whole life. But I have found such variety in the work I do as a university professor that I have not yet run out of new things to do. I teach a variety of courses on geology, and I conduct research on the San Andreas Fault and other active faults. I often begin my research projects by looking at aerial photographs and other remote sensing images, like LiDAR. I look for landforms that have been laterally offset by the fault, such as stream channels or alluvial fans. My students and I then spend time out in the field, making geologic maps of those offset landforms and looking for ways to measure their age so that we can determine how long it took for those features to become offset.

What are you hoping to learn from your research?

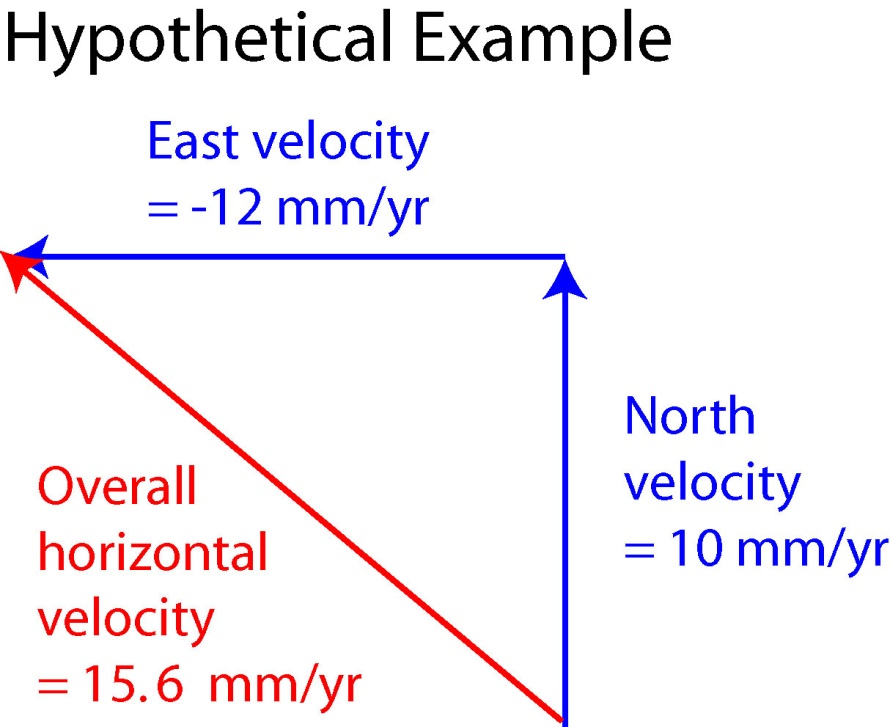

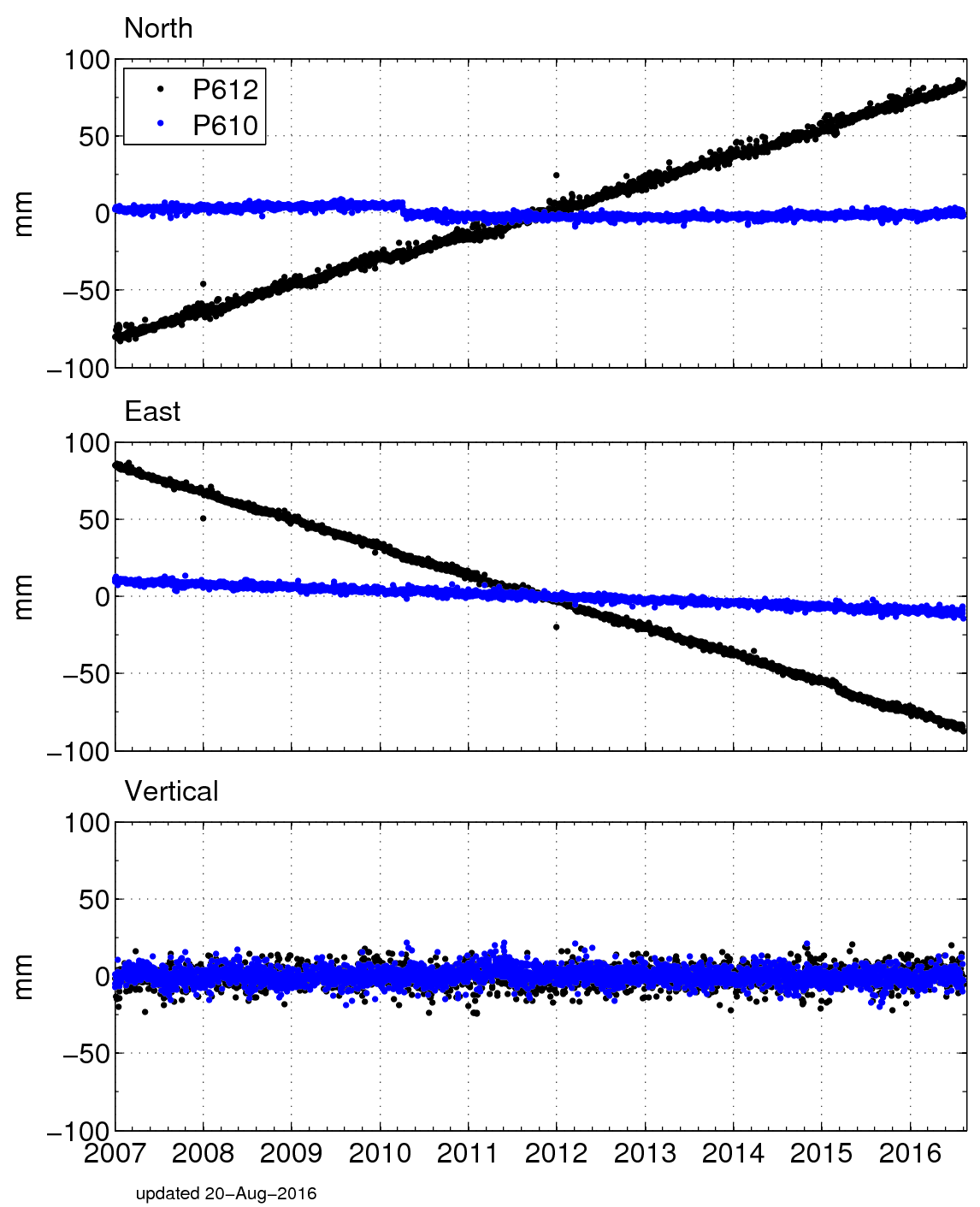

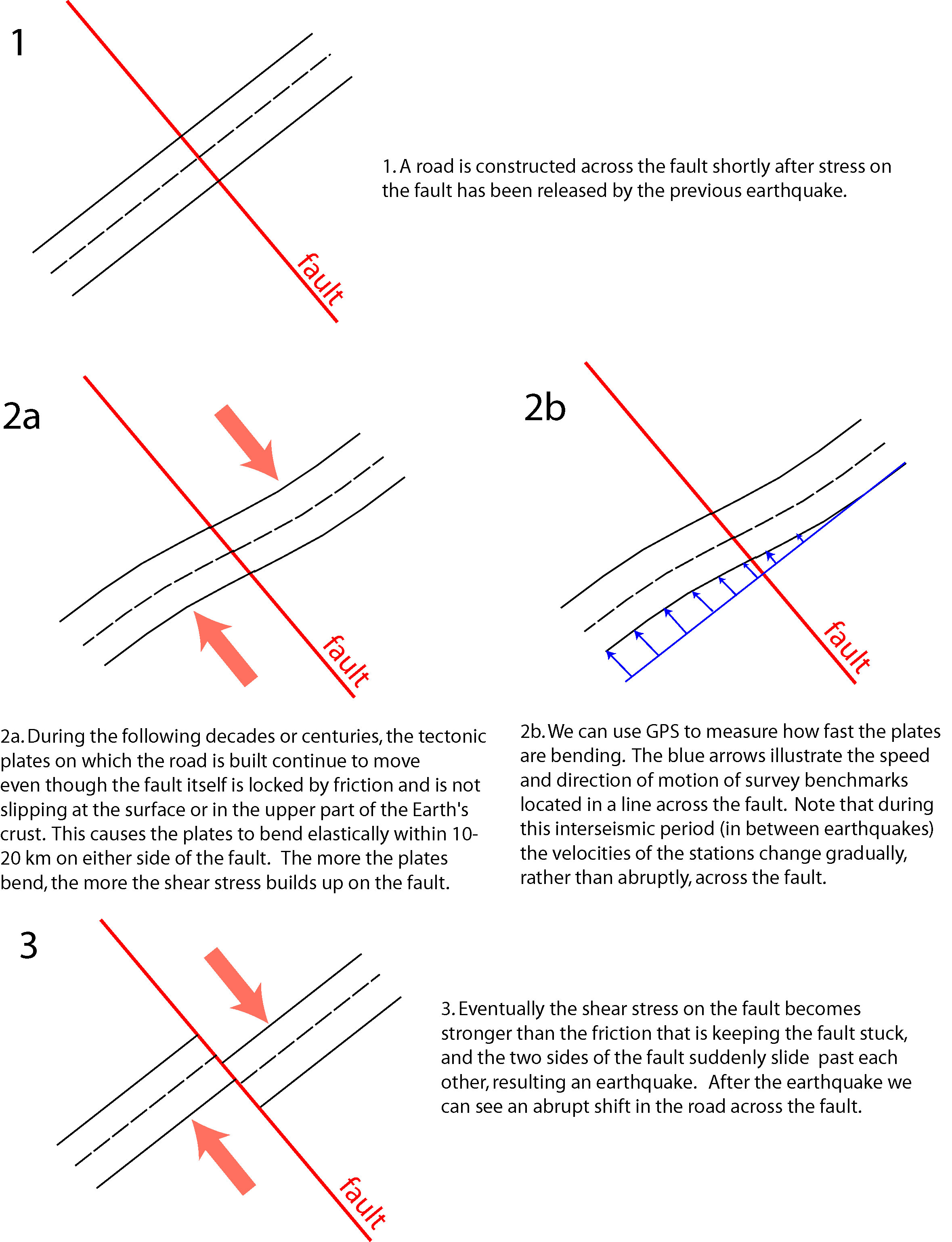

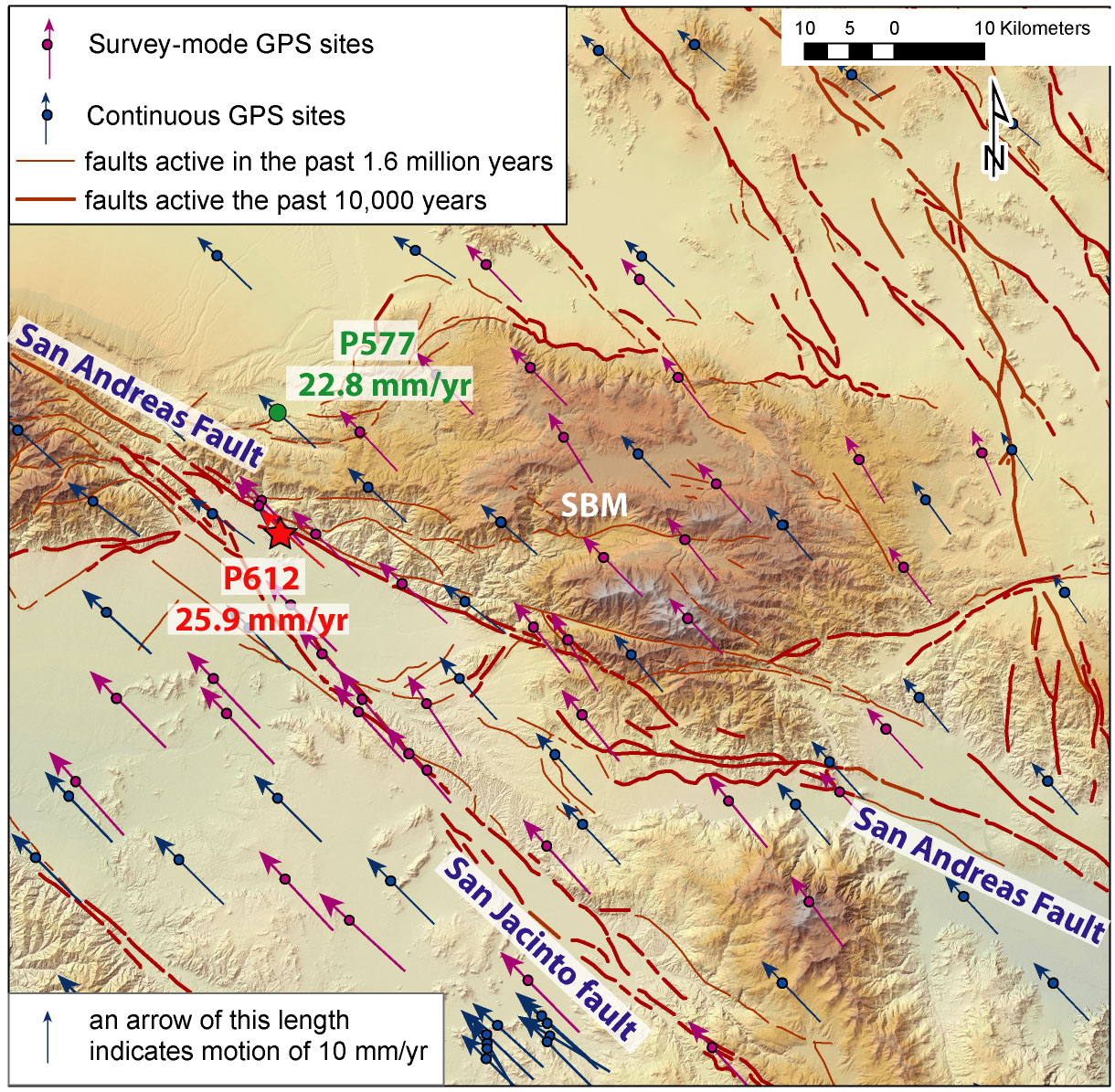

A primary goal of my research is to measure how fast the San Andreas Fault and other faults are moving. Using offset landforms, as described above, we can measure the long-term fault slip rate, averaged over thousands of years, as a result of many earthquakes. GPS gives us another, independent method of estimating fault slip rates. With GPS we can measure the bending of the tectonic plates over the past 10-20 years and then infer what rate of slip on the deep part of the fault, where the rocks are hot enough to flow, would cause the degree of bending that we observe at the surface using GPS. Knowing how fast the faults are moving is a vital piece of information for estimating the earthquake hazards of a region.

unavco.org.

unavco.org.